The

two main paradigms of dog training have never been fought out as much as they

are now. You only have to glimpse at social media to see the positive reinforcement

v’s balanced trainers, trying to battle it out, each insisting that their way

is the best.

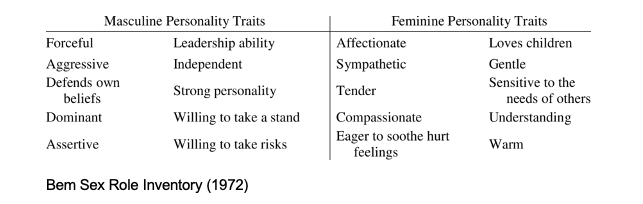

Balanced training has become quite a trend with high profile trainers gaining a pseudo-celebrity status on platforms such as Tik Tok and Instagram. These trainers who appear to have desirable masculine traits, use aversive training techniques to gain quick results, but as you will read, it is to the detriment of dog welfare.

They may use tools such as electric shock collars, prong collars and choke chains which they claim are effective and harmless, if used correctly, however those in the positive camp would argue to the contrary.

For those of us who work with clients and their dogs, it is imperative that we focus on the human as much, if not more, than the dog. To understand the human psychology and relationship between human and their dog is the key to finding effective solutions. To this end, we must take a trip down memory lane to understand the background of behaviour modification in humans to see how it translated to dog training.

In 1976, Lichstein and Shriebman published a paper in which they state:

“The use of electric shock in a punishment paradigm has continued to be a highly controversial issue in the treatment of autistic children. While the experimental literature argues for the effectiveness of the procedure for reducing maladaptive behaviors, some clinicians and researchers have expressed fear of possible negative side effects. The reported side effects of contingent electric shock were reviewed in an attempt to evaluate the validity of these fears. The review indicated that the majority of reported side effects of shock were of a positive nature. These positive effects included response generalization, increases in social behavior, and positive emotional behavior. The few negative side effects reported included fear of the shock apparatus, negative emotional behavior, and increases in other maladaptive behavior.” (Lichstein & Shriebman, 1976. P163).

The use of electric shock on autistic children still occurs in some Western countries, being described by antagonists as a form of torture that remains highly controversial.

Yet this procedure is still acceptable to some and indeed for many dog trainers to use on dogs too.

During the 1990’s, research demonstrated that positive behaviour intervention support was a more effective way of modifying behaviour. The motive for an unwanted behaviour was identified and steps taken to remove it. For example, a child who was afraid of the dark, would be given a night light rather than being punished. This sounds like common sense today and the thought of using electric shocks on neurodiverse humans is quite unbelievable. Imagine how a child must feel being subjected to this aversion therapy?

Balanced training has become quite a trend with high profile trainers gaining a pseudo-celebrity status on platforms such as Tik Tok and Instagram. These trainers who appear to have desirable masculine traits, use aversive training techniques to gain quick results, but as you will read, it is to the detriment of dog welfare.

They may use tools such as electric shock collars, prong collars and choke chains which they claim are effective and harmless, if used correctly, however those in the positive camp would argue to the contrary.

For those of us who work with clients and their dogs, it is imperative that we focus on the human as much, if not more, than the dog. To understand the human psychology and relationship between human and their dog is the key to finding effective solutions. To this end, we must take a trip down memory lane to understand the background of behaviour modification in humans to see how it translated to dog training.

In 1976, Lichstein and Shriebman published a paper in which they state:

“The use of electric shock in a punishment paradigm has continued to be a highly controversial issue in the treatment of autistic children. While the experimental literature argues for the effectiveness of the procedure for reducing maladaptive behaviors, some clinicians and researchers have expressed fear of possible negative side effects. The reported side effects of contingent electric shock were reviewed in an attempt to evaluate the validity of these fears. The review indicated that the majority of reported side effects of shock were of a positive nature. These positive effects included response generalization, increases in social behavior, and positive emotional behavior. The few negative side effects reported included fear of the shock apparatus, negative emotional behavior, and increases in other maladaptive behavior.” (Lichstein & Shriebman, 1976. P163).

The use of electric shock on autistic children still occurs in some Western countries, being described by antagonists as a form of torture that remains highly controversial.

Yet this procedure is still acceptable to some and indeed for many dog trainers to use on dogs too.

During the 1990’s, research demonstrated that positive behaviour intervention support was a more effective way of modifying behaviour. The motive for an unwanted behaviour was identified and steps taken to remove it. For example, a child who was afraid of the dark, would be given a night light rather than being punished. This sounds like common sense today and the thought of using electric shocks on neurodiverse humans is quite unbelievable. Imagine how a child must feel being subjected to this aversion therapy?

Using pain, torture, or humiliation to control behaviour is abuse, yet we still do it to non-human animals. So, lets take a deeper dive into why.

Courses that may interest you

The best instructors have designed the most motivating learning paths for you.

Working With Aggression

The Working with Aggression Course is a comprehensive educational programme for professional dog trainers and behaviourists, that will provide you with the required knowledge and skills for working with aggressive behaviours in dogs.

The Fallout Of Punishment & Negative Reinforcement

Punishment is known to achieve quick results but what are the long term implications and why is it not the best solution?

Animal Abuse & Inter-Human Violence

The Link Course is a fascinating journey that explores the relationships between animal cruelty and inter-human violence. It brings together information about the causes and the impact of animal cruelty and human violence.